Four axes: a framework for classifying quantum tech startups

And how to tell when regular startup lessons carry over to quantum tech—and when they don’t

One of the most interesting, but challenging, aspects of quantum technology is its diversity. Not only in the kinds of technologies being developed—computing, communication, sensing—but in the companies themselves, which differ in development speed, maturity, and business models.

I’m constantly learning how differently these companies operate, though my work with clients, through conversations with other folks in the industry, and from reading about startups and tech more broadly. While there hasn’t been much written about running quantum tech startups specifically, there’s a large body of material on running regular tech startups.

But to understand which lessons are likely to apply to which quantum tech startups, it’s useful to categorize these startups along several axes. That’s what I want to do in this article.

I’m specifically going to focus on startups that are building a product, rather than services or consulting companies. I’m using “startup” here in a specific way, which I’ve written about in more detail here.

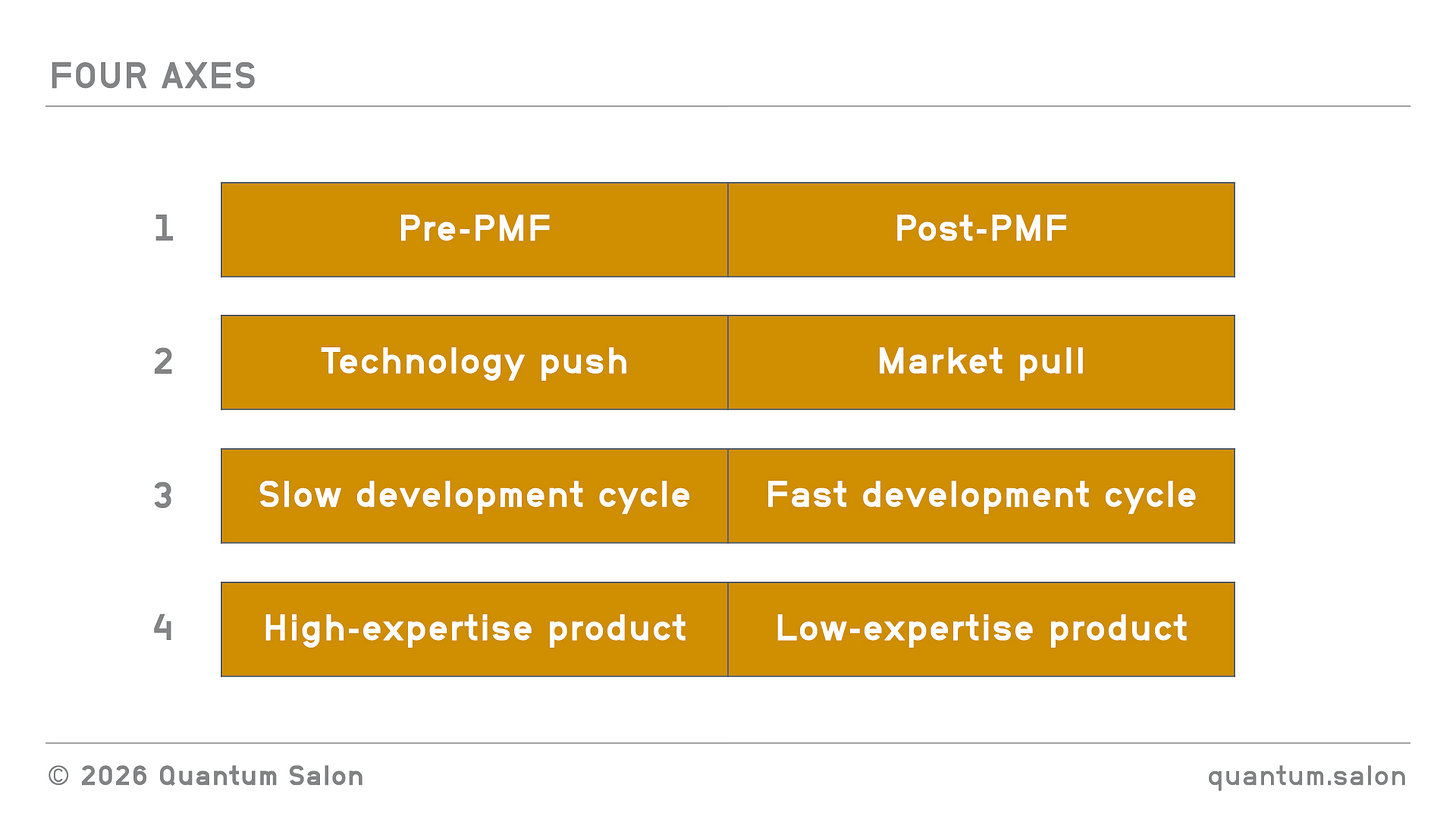

The four axes

When it comes to categorizing quantum tech startups, I’ve found four dimensions to be particularly useful. For the sake of discussion, I’ll describe them as binary (pre vs post, slow vs fast) but in practice they form a spectrum.

The four axes are:

Pre-PMF vs post-PMF (PMF = product–market fit)

Technology push vs market pull

Slow development cycles vs fast development cycles

High-expertise products vs low-expertise products

These are definitely not independent dimensions, but for the sake of simplicity, I’ll treat them as if they were.

A company’s position on an axis can change organically over time, or it can be the result of a deliberate decision.

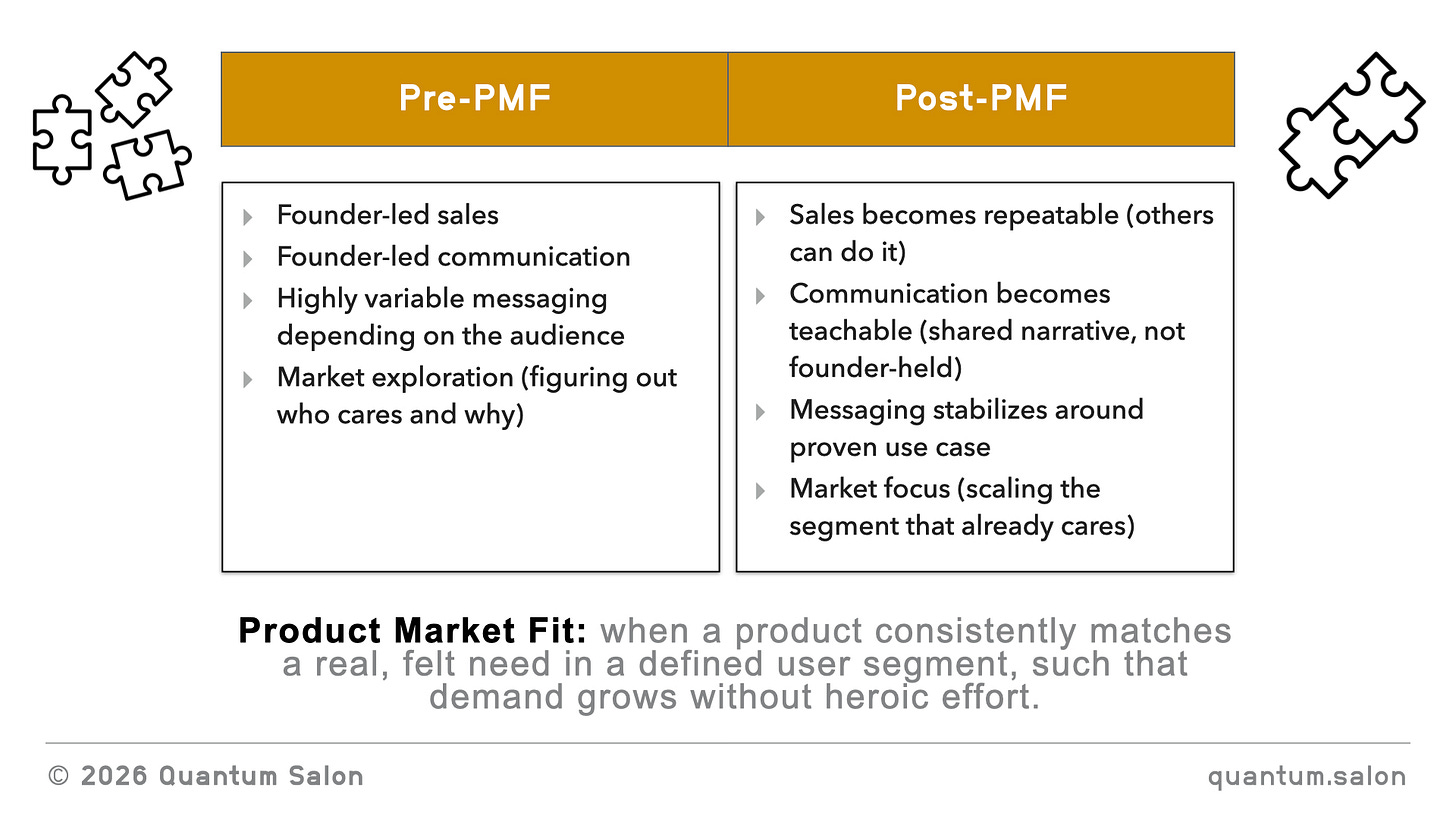

Pre-PMF vs post-PMF

This first axis is product-market fit (PMF). PMF is an important dimension for any startup, not just those in quantum tech.

If you google the term, you’ll get a wide variety of definitions. Here I define it as follows.

Product-market fit: when a product consistently matches a real, felt need in a defined user segment, such that demand grows without heroic effort.

For a pre-PMF company, sales and communication are usually founder-led. Everything is still evolving so it’s difficult to externalize it enough to be able to get outside help. Messaging tends to vary a lot, not only depending on who the founders are talking to, but also over time, as the founders adapt what lands and what doesn’t. In this stage, the company is still figuring out who actually cares and why.

Post-PMF, sales become more repeatable, in the sense that people other than the founders can do it. Communication becomes teachable, with a shared narrative, rather than something that lives only in the founders’ heads. Messaging stabilizes around a proven use case, and the focus shifts from exploring the market to scaling the segment that already cares.

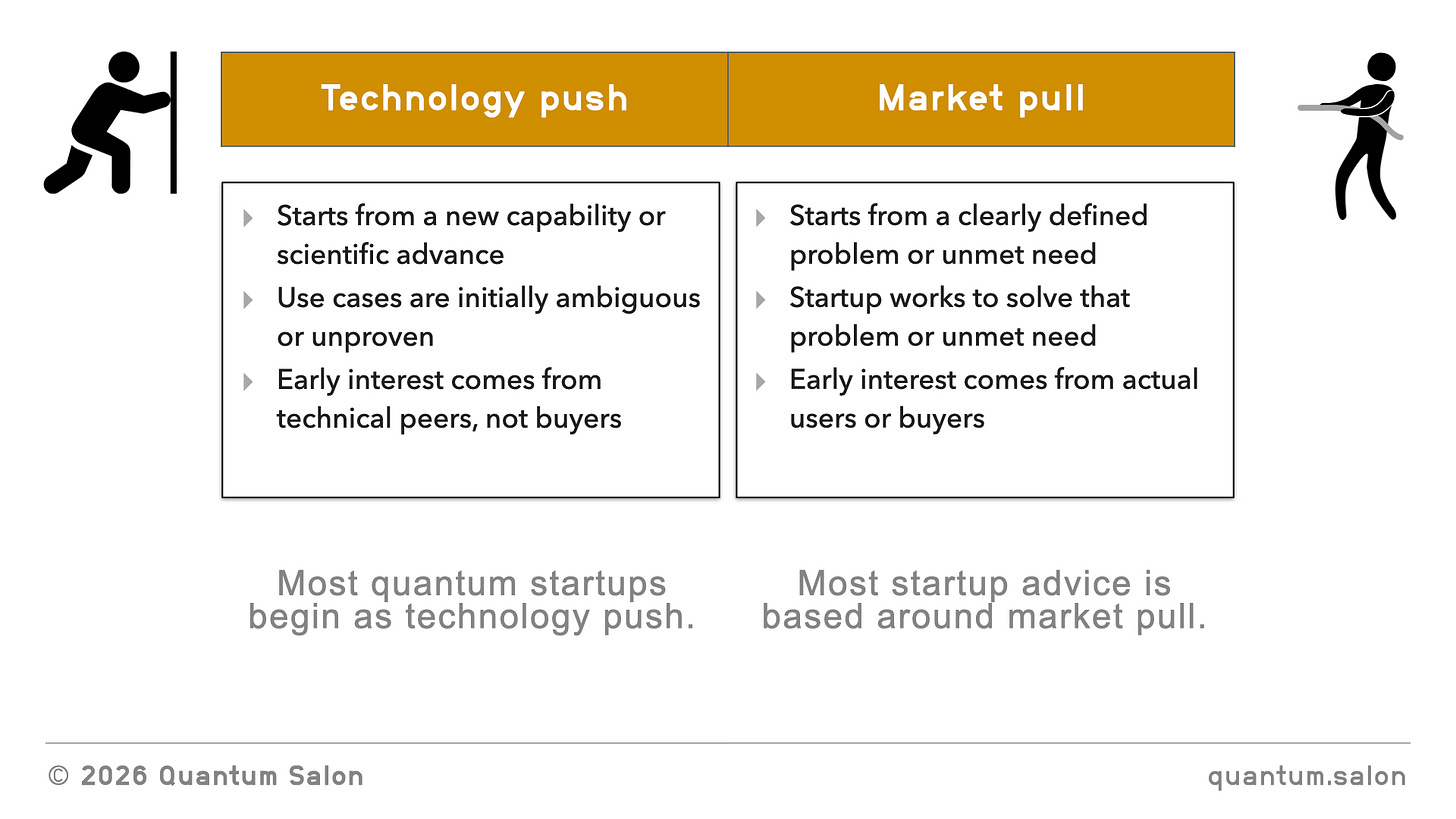

Technology push vs market pull

The next axis tell us whether a company starts from a market need or from a new technical capability.

In a market-pull startup, the process usually begins with a clearly defined problem. The startup exists to solve that problem, and early interest comes from people who might actually buy the product.

In a technology-push startup, the process usually begins with a new capability, often rooted in a scientific or engineering advance. In the early stages, it’s not clear what the use cases are, so there are no obvious buyers. The people who are most interested in what the company is doing are other researchers and technical peers.

There exists a large body of startup literature (books, podcasts, blogs, founder lore, etc) but most of it is written with market-pull in mind.

Not in the sense that it assumes that a startup is market-pull, but in the sense that it assumes that a startup has the ability to become market-pull and therefore it should. You often here things like:

There’s nothing worse than being a solution in search of a problem.

This is great advice for startups based on mature technologies, like software, who can build what buyers want in a relatively short amount of time.

It’s more difficult to do for deep tech startups, especially those with long-development cycles.

That brings us to the next axis.

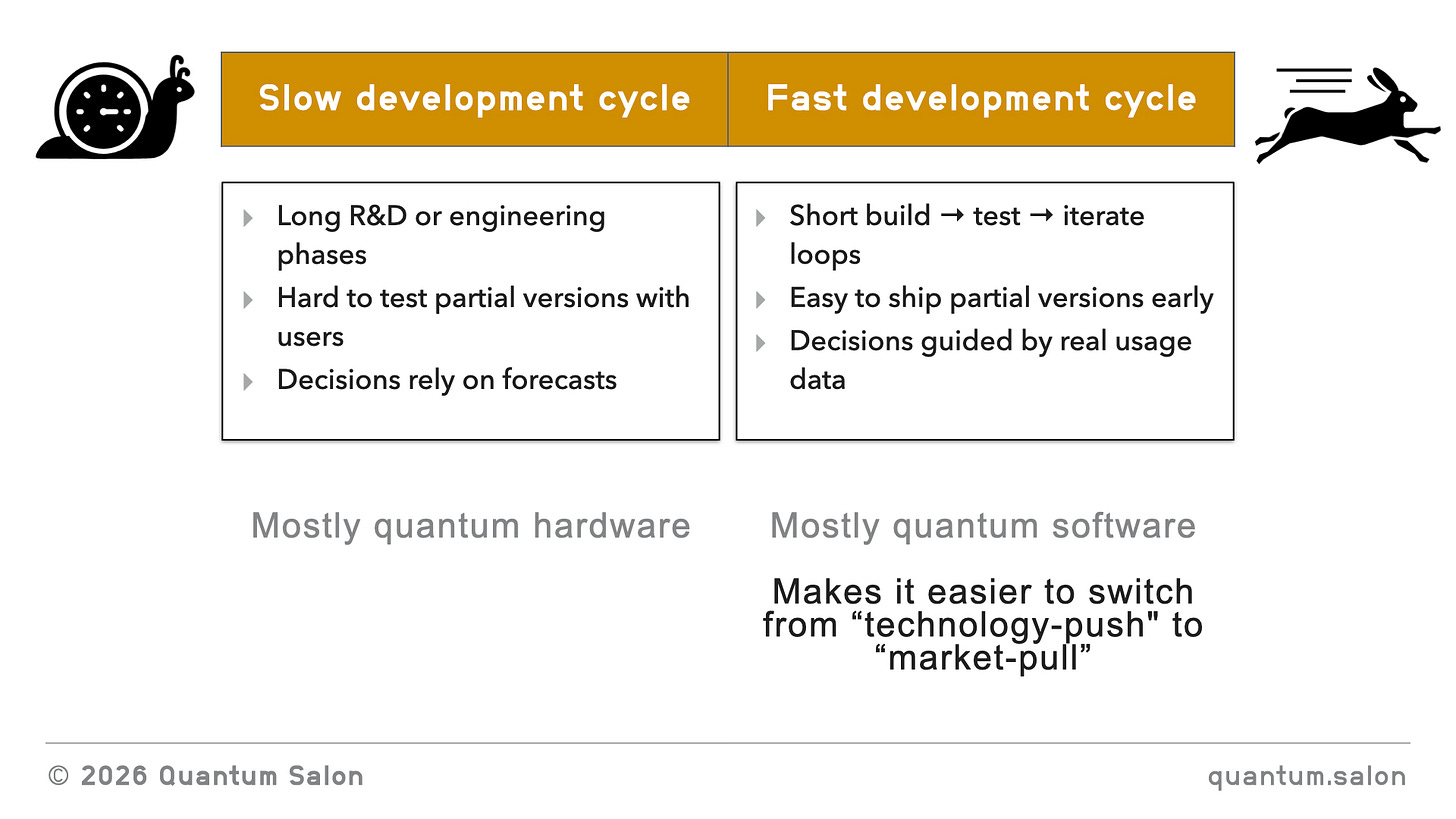

Slow development cycles vs fast development cycles

Some products allow for short build–test–iterate loops. You can ship partial versions early, learn from real usage, and make decisions based on data.

Others require long periods of R&D or engineering before anything usable exists. Partial versions can be hard to test with users, and decisions rely more on forecasts and judgment calls.

A lot of quantum hardware typically has slow development cycles. Quantum software, on the other hand, can have fast development cycles.

Again, the large body of startup literature implicitly assumes fast development cycles. But if your development cycle is slow, not everything from the startup canon will be relevant. For example Agile methods tend to make sense when you can iterate quickly, while more sequential approaches like Waterfall might be better when development takes longer.1

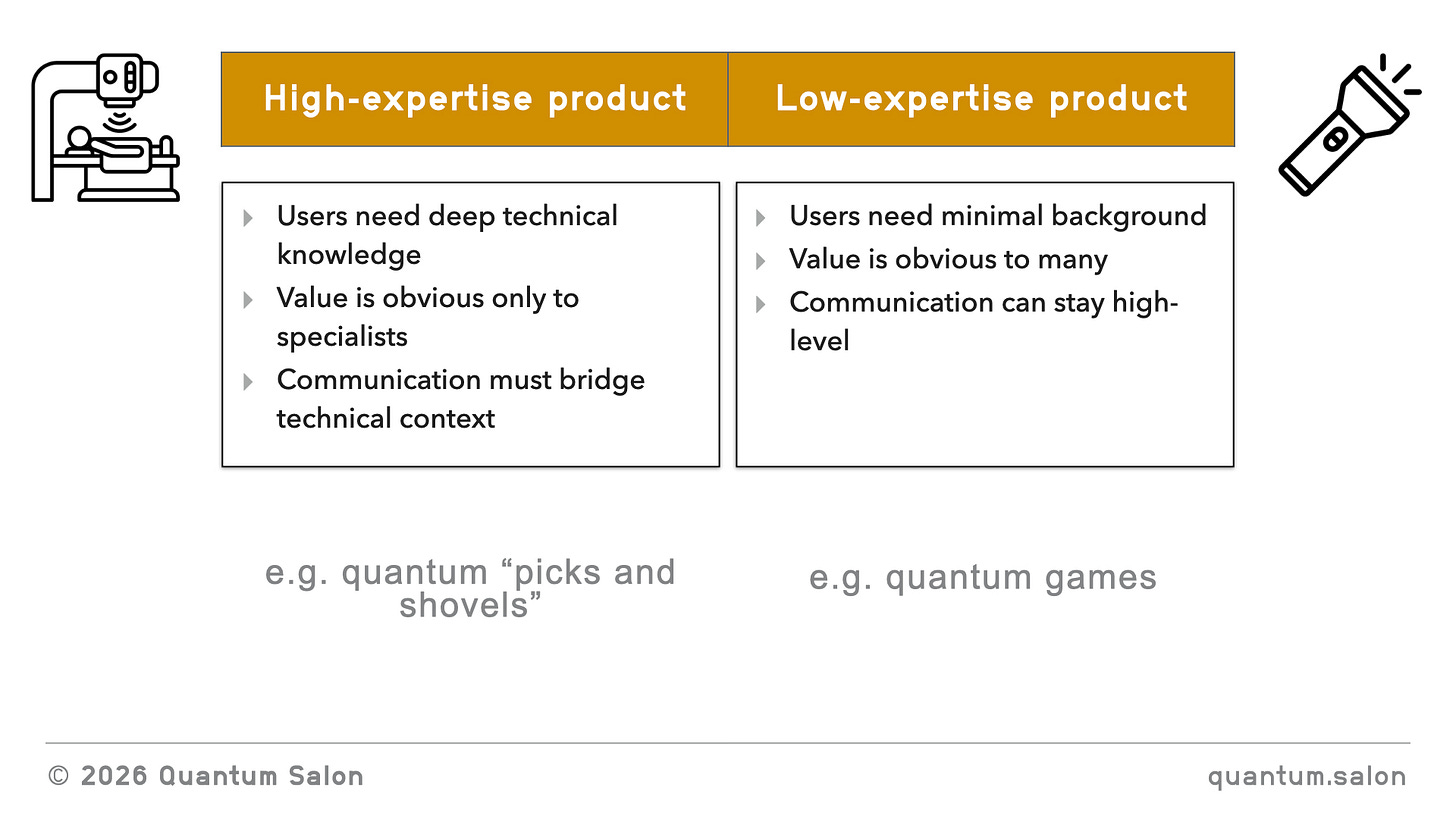

High- vs low-expertise products

The final axis is about who your product is actually for.

Some products require deep technical expertise to use. Their value is obvious mainly to specialists, and communication has to match that.

Others require relatively little background. Their value is more immediately visible, and communication can stay higher level.

Specialized quantum products being sold to quantum companies tend to fall into the high-expertise category. Other products, like quantum-themed games sit much closer to the low-expertise end.

Putting the axes together

If you’re a nerd, like me, you might have had this thought: 4^2=16. That’s sixteen combinations!

You might even go as far as considering what each of these combinations means.

It turns out that not all combination are equally interesting, but some of them represent some interesting scenarios.

Let’s take a look at these.

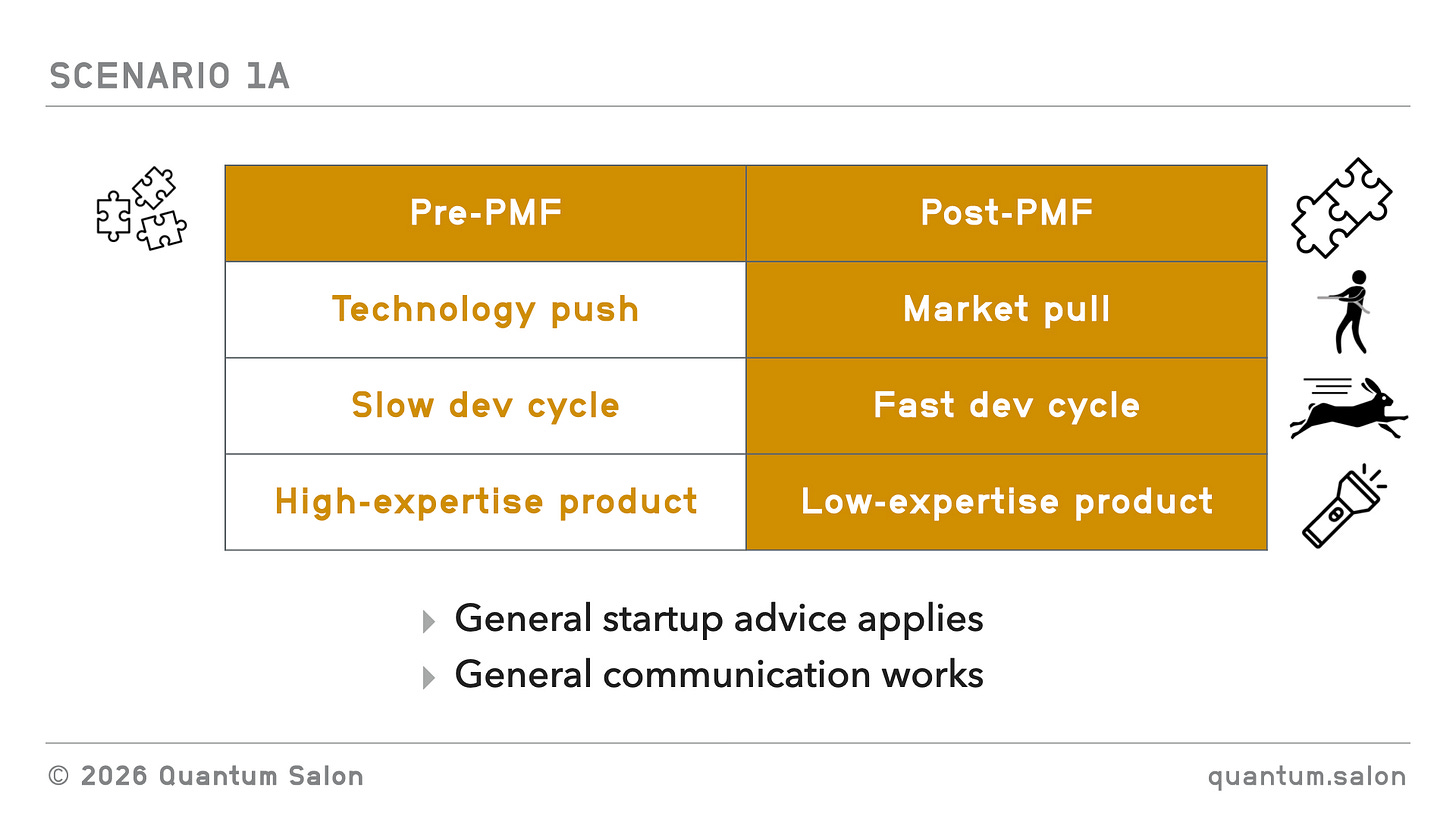

Scenario 1A: Conventional broad-market startup

In this scenario, the company is market pull, has a fast development cycle, and is building a low-expertise product. It may be pre- or post-PMF, but it effectively looks like a regular tech startup from Silicon Valley.

How a post- or pre-PMF startup operates is going to vary quite drastically. Fortunately, there is a tonne of advice out there for both phases, and a tonne of people who have built such startups for you to talk to, and that advice will apply if the startup is in Scenario 1A.

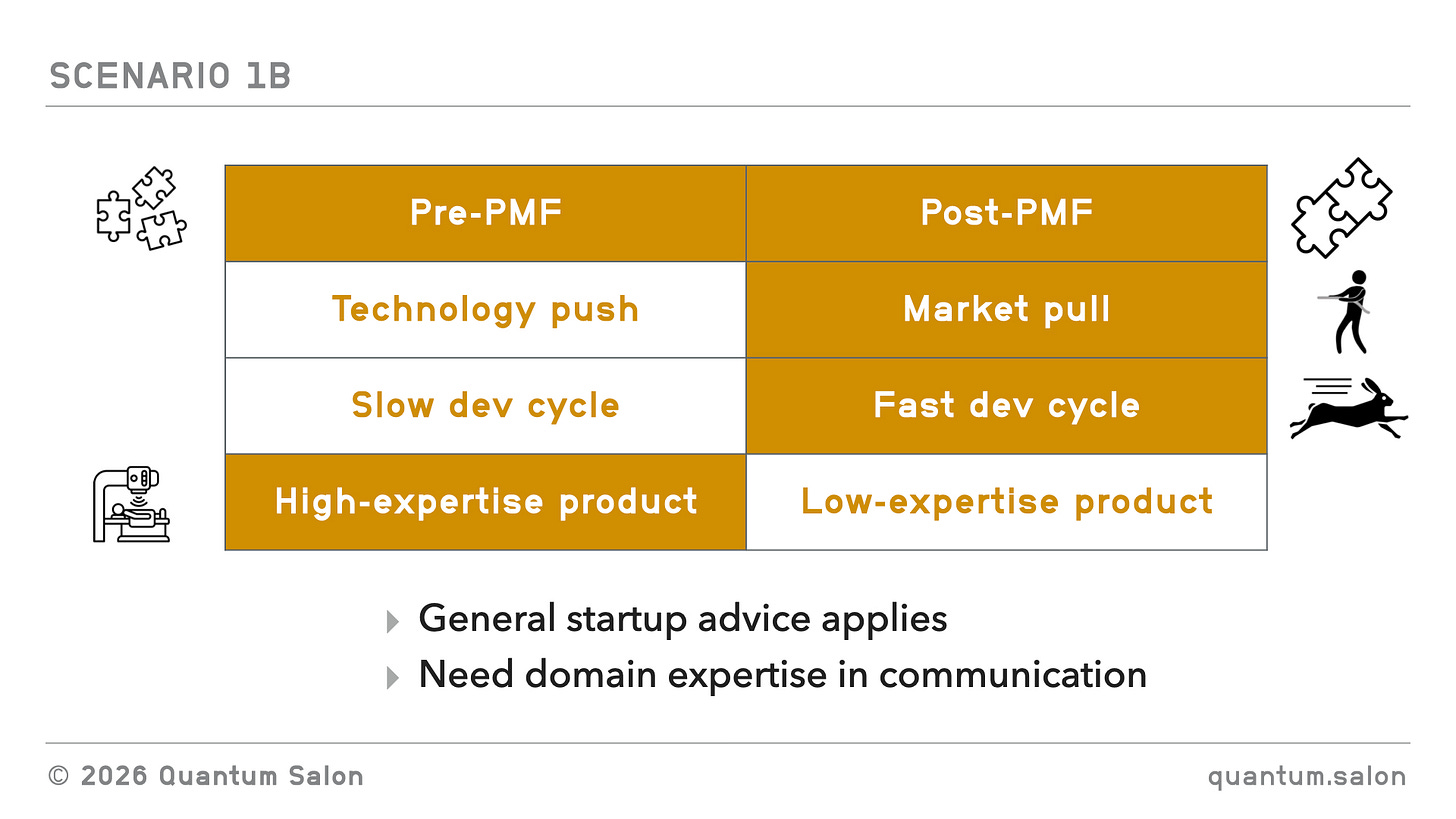

Scenario 1B: Conventional expert-user startup

This scenario is almost the same as above, except you have a high-expertise product. So for example, you’re selling software that will be used by technical folks inside a company, or researchers at a university.

The main challenge in this scenario is communication.

Because the product requires deep domain knowledge, the messaging to technical customers has to be quite specialized. At the same time, the product needs to be explained in much plainer terms to less technical stakeholders, like investors. Doing both well usually means having someone with real domain expertise who can also translate that work without flattening it.

This is the kind of communication work we do at Quantum Salon.

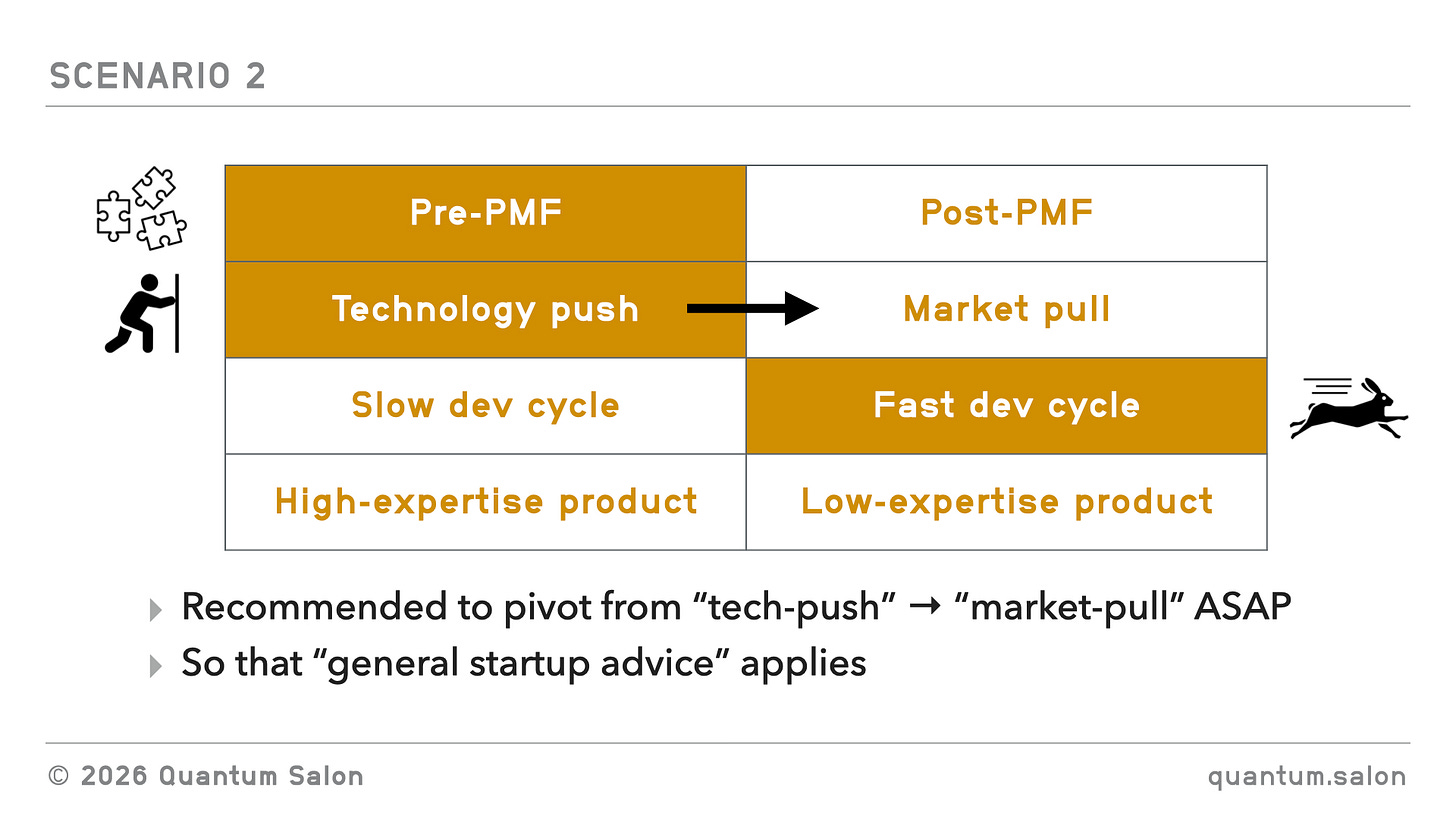

Scenario 2: Conventional tech push startup

In this scenario, the company is pre-PMF, technology-push, but has a fast development cycle. Even though the starting point is a new capability rather than a clearly defined market need, the company can iterate quickly and learn from feedback.

Because of that, these companies often end up moving toward a market-pull approach.

You see this a lot in the quantum tech ecosystem, especially with algorithm-focused startups. They might begin with a specific quantum algorithm aimed at a particular domain, like drug design or optimization. But after talking to customers, they figure out that the original use case isn’t very compelling. At the same time, through these conversations, they also discover problems that customers do care about. The startup then shifts its focus to those problems, often trying to solve them with different techniques like classical or AI-based algorithms rather than strictly quantum ones.2

That move is sometimes mocked, particularly in academic circles. But in practice, it can be the right business decision. It increases the chances that the company survives, and it doesn’t necessarily mean abandoning the original research. Some companies continue working on the original quantum stuff in the background, for later, while building something that people want to use now.

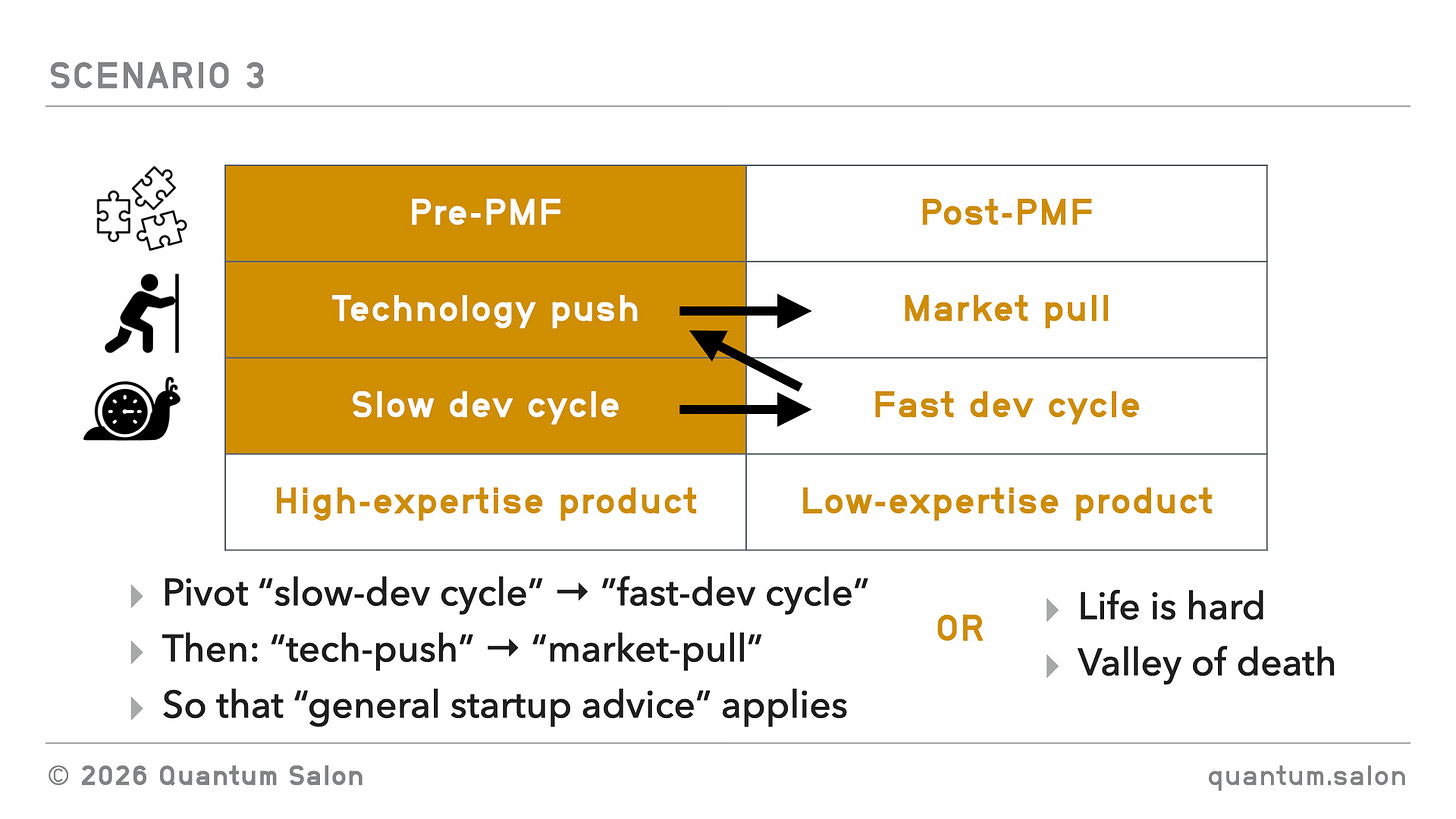

Scenario 3: Deep tech startup

In this scenario, the company is pre-PMF, technology-push, and operating with a slow development cycle. This is where a lot of deep tech startups find themselves.

It’s a really tough spot to be in. They have a cool technology, but it’s going to take a really long time to develop it. It’s not clear what the product is. They might not even know what the market is, or if there even is one. But they founders have started a company and need to figure out how to fund it during development.

How do they deal with this? I’ve seen it play out in two main ways.

The first way is to move toward market pull. That usually means the company can’t stay in a slow development cycle. It has to find ways to shorten the cycle so that they can iterate faster, which may mean scrapping/putting on hold most/all of the technology they started with. Once they do that, they can think about the market, adapt to it, and do the usual startup things.

You see this in quantum tech when companies start out building hardware, but also have a software, cloud, or services component. At some point, they decide to drop the hardware effort and focus entirely on the software or cloud product. As in the above scenario, sometimes they can continue working on the original quantum stuff in the background, but it’s more difficult when it’s a capital intensive technology like hardware.

The second option is to not do that, and stay technology-push with a slow development cycle. That’s the scenario that most quantum hardware companies, that choose to continue to focus on hardware, are in.

If you take this route, you’re deep in the Valley of Death, and life is hard.

Some regular startup lessons might not apply

(This section is my own, non-standard, view)

I think for companies that choose to remain in Scenario 3, some parts of the startup cannon stop being helpful, especially the idea that a company should focus so heavily on customers/end-users and use cases. If it’s going to take five to ten years to develop a product, then asking customers what they want now isn’t going to be very productive. Of course, the company still needs to believe that a useful product exists at the end of the path, and work towards it, but it’s like steering a big ship towards that outcome rather than building it incrementally based on what customers say today.

Things also get awkward from a communication perspective when tech-push companies, that are still far from having a product3 (let alone product–market fit) present themselves as if they were market-pull. They end up squeezing what they’re doing into the language of products, users, and applications that don’t yet exist. At best, it’s confusing. At worst, it raises questions about clarity, competence, or whether the company respects all of it’s stakeholders. All of these undermine trust.

I understand why there is pressure to focus on customers prematurely, because that’s the way everyone is used to thinking in business. But I believe that long-term outcomes would be better for Scenario 3 companies if they focused their communication on the stakeholders that actually matter for survival during the development phase: investors, corporate partners, academic collaborators, policymakers, and future technical hires.

The task is to explain why the technology matters and to make a credible case that a market could exist, without pretending that concrete use cases or users are already there. That requires understanding what each of these groups cares about, what would make them want to engage, and how to communicate with them in a way that stays internally consistent.

That kind of communication depends on a deep understanding of the different actors in the quantum technology ecosystem, and how they relate to one another. This is also the kind of communication we do at Quantum Salon.

Choosing which lessons to apply

I find this classification really useful in understanding why different companies do what they’re doing, and to reason about what I think they should be doing.

If you’re working with (or for) startups in the quantum space, it might also help you decide which lessons are worth paying attention to, and which ones assume conditions that don’t (yet) hold for that company. At the very least, it should help you pause and run a sanity check to see if they do.

I only covered several scenarios (combinations of the four axes) that are most interesting to me. I wonder if there are others that you find interesting.

Quantum Salon Insights is an independent reader-supported research project focused on making sense of the quantum tech ecosystem.

Here we explore the ideas, patterns, narratives, and structural misalignments that show up across quantum tech and adjacent deep-tech fields.

To receive new posts and support this work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I find it interesting that now with all the AI-assisted coding tools, the methodologies are shifting back towards Waterfall style planning.

A fun thing to do is to use the Wayback Machine to see how a startup’s website changed over the years to see this evolution.

Whether existing quantum computers can reasonably be called a product depends on who the users are and what they’re actually using them for.

I think it makes sense to treat them as a product when the market is quantum researchers and the use case is research.

You could probably also make a case when the market is commercial enterprises and the use case is building optionality as part of a longer-term quantum program.

But if the market is commercial enterprises and the use case is solving concrete business problems, then the product doesn’t really exist yet. I think it would be hard to argue that we can have a product in that case before fault-tolerant quantum computing is available.