Quantum tech for general audiences

The interesting part isn’t the cat

Greetings from Barcelona. I’ll be attending the Quantum Education Summit tomorrow. I thought this would be a good time for me to write down my thoughts on how we should (and shouldn’t) talk about quantum technology with general audiences.

As an aside, when I moved from academia to industry, I found it funny that people used the term quantum like it’s a standalone thing. Because technically, it’s supposed to be a modifier: quantum physics, quantum computing, quantum sensing.

Inevitably, I adopted this lingo too, but I think it’s related to my pet peeve about how people talk about quantum tech, where they conflate different “quantums” in an unproductive way. Specifically when they conflate quantum foundations, quantum physics/engineering, and quantum information.

In this post, I’ll describe how I see the distinction between these fields, and make my case for why it’s helpful to maintain that distinction when discussing quantum tech with general audiences.

But first we should start with quantum theory.

Quantum Theory

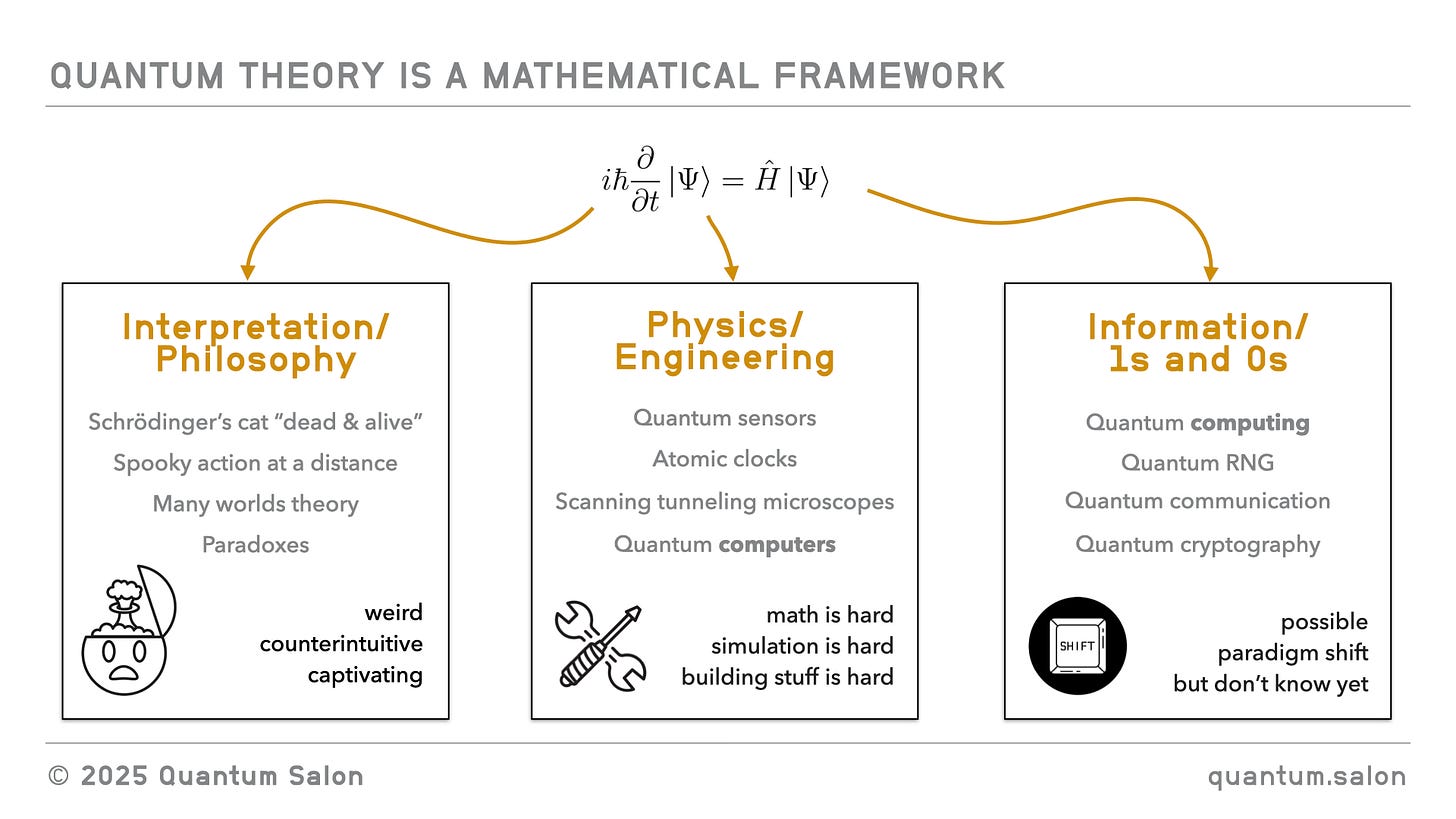

Quantum theory is a set of equations and rules that tell you how a system behaves. It’s a mathematical framework. On its own, it doesn’t tell you what the system is—an atom, a photon, a qubit, a molecule, a cat, consciousness—it just gives you the machinery for calculating how that thing evolves, interacts, or gets measured.

That mathematical framework branches into different disciplines depending on what systems or questions you apply it to.

Quantum Theory applied to Philosophy = Quantum Foundations

Quantum Foundations is the field of research where people ask questions like: what does the wavefunction mean? It’s where people talk about Schrödinger’s cat, Wigner’s friend, many worlds, spooky action at a distance, and other things that seem like paradoxes. This is the stuff that captures the imagination, both for scientists and non-scientists alike. Understandably, it’s the stuff people want to talk about.

Quantum Foundations is a very important academic discipline—one that I would like to work in if I ever go back to research again—but you don’t need it to understand quantum tech. In the physics community, there’s a famous expression for putting aside philosophical questions in favour of more practical applications. That expression is “shut up and calculate”.

Quantum Theory applied to Physics / Engineering = Quantum Physics / Quantum Engineering

“Shut up and calculate” is the physics and engineering branch. Here, people use the same equations from quantum theory to understand the physical world and to design and build new technologies like quantum sensors, atomic clocks, scanning tunneling microscopes, and of course quantum computers. The questions are practical: can we model this system, can we fabricate this thing, can we make it stable?

The work done here is also very important, but I don’t think it’s particularly exotic. I don’t mean that in a disparaging way (this branch is where I spent most of my academic career, and I think it has immense value). And of course, when you dig deep enough, things like new quantum materials are exotic, but in the grand scheme of things, I don’t think they’re more exotic than the most interesting processes in other parts of physics, or chemistry or biology. They’re not “capture the imagination” exotic like the idea of a cat being alive and dead at the same time or parallel universes.

I would say the main distinguishing feature of this branch is that it’s really hard. The math is really hard. The simulations are really hard. The building the stuff and making it work is really hard.

Quantum Theory applied to Computer Science = Quantum Information

The third relevant branch is computer-science. In this branch, parts of quantum theory are interpreted as carriers of information. Here we have quantum computing (i.e. how to use a quantum computer, rather than how to build one), and other quantum information protocols such as quantum communication, quantum cryptography, quantum random number generation.

The thing that’s special about this branch is that there is real potential for a paradigm shift, with the development and application of new quantum algorithms and other quantum information protocols. You could argue that the paradigm shift already happened with the development of algorithms like Shor’s and the idea of quantum simulation, but these are academic results. In the grand scheme of things, in terms of impact on the general public, a paradigm shift remains to be felt (or even adequately imagined).

So it’s a bit of a Catch-22. Quantum computing could be HUGE. Or it could be a nothing-burger. It’s really hard to come up with new algorithms and applications in the abstract. Only a few people around the world are able to do that kind of work. The hope is that if a large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computer is built, and people start playing around with it, they will discover amazing things for it to do1, things that have the potential to change the world. But we don’t know if they will. And in order to build these devices, it requires billions of dollars of investment and more time than people like to admit. So the challenge is how to make the case for that investment.

Incidentally, here’s a relevant quote I saved a while back:

Mr. Altepeter [program manager for DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative] said that among the 10 smartest physicists he knows, “half are convinced this will be the most important technology of the 21st century and will revolutionize everything we do. The other five are convinced you’ll never build a quantum computer no matter what you do” – or that if one is built, “it would never be more useful than your laptop for solving a real problem.”

The communication challenge

I think the potential of quantum computing has absolutely captured the imagination of academics who understand how quantum algorithms and quantum simulation differ fundamentally from their classical counterparts. But it’s really hard to communicate that potential to people who don’t have a PhD-level understanding of quantum theory or quantum information theory.

So you get this bizarre mix of communication blunders:

Academics trying to explain how the algorithms work, and ultimately losing people in the details.

The use of imprecise or unsatisfying metaphors for how the algorithms work, which then get twisted when repeated by others, to the chagrin of academics.

Exotic concepts from quantum foundations being used to motivate why quantum technology is exciting, even though they aren’t really relevant as motivation.

This idea that we should stop talking about the technology and focus on the specific benefits of quantum computers for users, which is premature, and so it comes out as hype.2

The big picture

I know I’ve been terribly imprecise on some of the details here, and experts reading this are grimacing. But my point is that certain details aren’t important to someone coming from the outside who wants to understand what all the fuss is about quantum technology.

What’s important is the big picture, and understanding which parts of it are or are not relevant, so they can decide where to dig deeper.

Quantum foundations is awesome. If you’re interested in it, absolutely learn about it. But it’s not the reason why quantum technology is important for society.

Quantum physics/quantum engineering and quantum information are much more closely connected to each other than they are to quantum foundations, but I think they’re still distinct in the way in which they’re exciting and the way in which they have potential for impact.

Generally speaking, I don’t think the application of quantum physics/quantum engineering to technology is more important than the application of classical physics/classical engineering to technology. But it isn’t less important either. It’s complimentary and we should absolutely invest in it (a lot).

But the potential that quantum information has (quantum computing and other protocols) is different, and I think we need to find a better way of communicating to general audiences why academics are so excited about it, without leaning on conceptual paradoxes3 or resorting to hype. I’ll take a stab at this in an upcoming post (and if you know of some examples where people have done this well, I’d love to see them!).

I think if we don’t do this, we risk disillusionment. If people get excited about quantum technologies for the wrong reasons, and then discover that those reasons don’t stand up to scrutiny, then it will be (justifiably) difficult to convince them of the real value of these technologies.

Quantum Salon Insights is an independent reader-supported research project focused on making sense of the quantum tech ecosystem.

Here we explore the ideas, patterns, narratives, and structural misalignments that show up across quantum tech and adjacent deep-tech fields.

To receive new posts and support this work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This isn’t a crazy expectation. We see this happening with AI now. People who get their hands on something are much better at figuring out how to use it than people trying to figure it out in the abstract: “In August, MIT’s NANDA project published a study about efforts to adopt AI by American businesses. They found that “95% of organizations are getting zero return” from enterprise investments in IT. AI skeptics have been citing this statistic ever since. After all, if 19 out of 20 AI implementation projects fail, that’s a huge problem for boosters who claim AI is on the precipice of changing the world. . . Read closer, however, and you see that the companies were benefitting from AI, just not as part of official corporate software projects. “AI is already transforming work, just not through official channels,” the researchers wrote. “Our research uncovered a thriving ‘shadow AI economy’ where employees use personal ChatGPT accounts, Claude subscriptions, and other consumer tools to automate significant portions of their jobs, oXen without IT’s knowledge or approval.”

I like Google’s approach to this: “Instead of starting with a vague business problem, which has had limited historical success, we should focus on getting algorithms to a level of proven advantage (clearing Stage II) and then actively search for a real-world application (Stage III). In addition, a useful solution should be verifiable to lead to a practical application.”

I know that David Deutsch invented quantum computing when thinking about many worlds. I know that quantum foundations, quantum physics/engineering, and quantum information are all ultimately connected via quantum theory, and building a quantum computer might teach us something about quantum foundations. But I think those connections are mainly important to practitioners, and they’re distracting (or potentially even misleading) for general audiences who are trying to get a handle on quantum tech.